Total star rating: ★★★½

The works: ★★★★

The show: ★★★

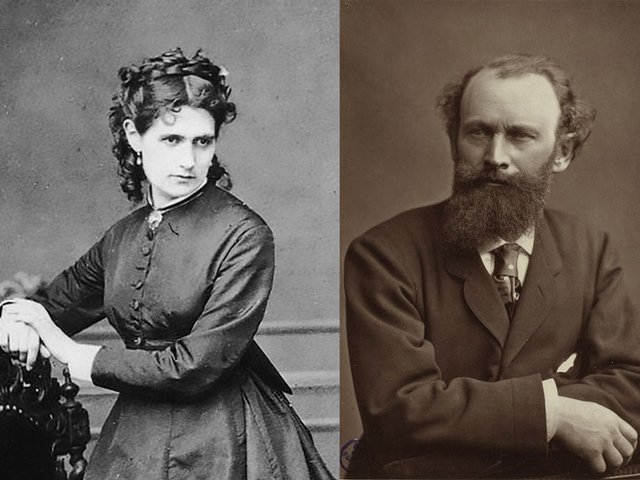

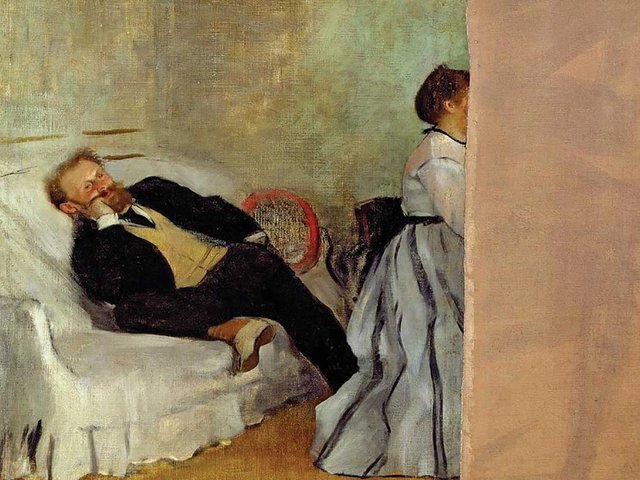

Around halfway into Manet & Morisot at the Legion of Honor in San Francisco, the paintings of Édouard Manet (1832-83) and Berthe Morisot (1841-95) begin to look surprisingly alike. The two French painters seem at this point to be looking at the same things in similar ways. The twist is that she was not inching closer to him, but he was approaching her. Even though Morisot was Manet’s junior, one of his favourite models, his close friend, his admirer (though never his student) and eventually his sister-in-law through a practical marriage to his younger brother Eugène, she emerges at this point as a sort of artistic beacon for Manet.

The convergence can be seen most dramatically in the pairing of Manet’s Before the Mirror (1877) and Morisot’s Woman at her Toilette (around 1875-80). His painting shows a woman in her dressing room from behind, as she gazes into a mirror and adjusts her corset. Instead of his usual palette, with those blacks and browns from Goya and Velázquez, Manet here chose lighter colours, like icy blues and peachy whites, and used a looser, more fluid, brushstroke—all typical Morisot. This is evident in her own toilette scene, where the murky white swirls of the woman’s dress continue onto the wallpaper, obliterating the clear delineation between figure and background. Despite his penchant for solid-looking forms, Manet too has let the white streaks defining the skirt spill over into the background. He seems to be taking his cue from Morisot, shifting from his realist origins to embrace a hazier, more atmospheric—many would say truly Impressionistic—aesthetic.

The twist is that she was not inching closer to him, but he was approaching her

Four seasons

Soon comes an even more explicit example of Manet following in Morisot’s footsteps. Among her paintings in the fifth Impressionist exhibition in Paris in 1880, which he saw, was a pair of oil-on-canvas portraits titled Summer (1880) and Winter (1880), representing allegories of the seasons. Only they are modern, urban allegories, where the model’s chic Parisienne fashions—a ruffled silk cream-coloured blouse for summer, a dark olive coat and muff for winter—announce the change in seasons. In 1881, just two years before his death from syphilis complications, Manet began work on two portraits at the same scale, of models Jeanne and Méry. His family believed they were meant to represent Spring and Autumn, and titled them posthumously as such.

Manet & Morisot makes a persuasive case that Manet created these works to complete Morisot’s series, and it shows all four seasons—the capstone to their artistic dialogue—together for the first time. The exhibition also points to one reason why Manet’s work resembled Morisot’s in his final years: he favoured simpler, single-figure studio portraits and plein-air, garden paintings while he struggled with the neurological effects of syphilis.

As the curator Emily A. Beeny writes in the catalogue: “In the last years of his life, as his illness restricted Manet’s daily movements to his home, his studio, and the suburban houses where he spent his summers, his pictorial world came to look more like the one Morisot had always inhabited; the Paris of a late 19th-century male invalid was not so different from that of a late 19th-century lady.”

One challenge in organising this exhibition, which is very loosely chronological, was how to make the narrowing scope of Manet’s painted world, which was initially dismissed as too frilly or feminine, seem substantial. The other, even bigger, challenge: how to pair earlier work by the two artists without overshadowing Morisot, whose paintings tend to be more intimate in scale and more subtle in their effects.

The opening gallery does not have this problem. It consists mainly of Manet’s keenly sensual portraits of Morisot. The centrepiece is The Balcony (1868-69), his multi-figure composition that shows a dark-eyed Morisot looking out over a green balcony railing with a serious case of ennui. (One of Monet’s personal favourites, he kept this canvas until his death, when it was purchased by another lover of balcony scenes, Gustave Caillebotte.) The trouble starts in the second gallery, which contains more direct Manet and Morisot comparisons, from their city views of Paris to various harbour and beachside scenes. Here Manet’s paintings eclipse hers in size, drama and power, the way an extrovert outperforms an introvert at just about any public gathering.

Structural sexism

It is now clear to me why curators have already delivered on Manet/Degas, Manet/Velázquez and Manet/Monet surveys, but have taken so long to give us Manet/Morisot. For starters, his canvases are significantly larger, reflecting the support he received from collectors and dealers, while Morisot as a woman struggled to maintain—and communicate—her identity as a serious artist. In his book Paris in Ruins, the art critic Sebastian Smee described both her depressive episodes and her fiercely competing demands: her decorum versus her ambition and the expectation of marriage versus her desire to remain single and single-mindedly devoted to her art. “The various threads of Berthe’s predicament seemed to be flexed against each other in a self-tightening knot,” he writes, offering an apt image of the binds of structural sexism. (Smee also notes that Morisot was “in love” with Manet, who was married, but Beeny pushes back on that assumption for lack of documentary evidence.)

Manet’s The Balcony (1868-69), which depicts Morisot seated at the front

© RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY

Furthermore, Morisot’s early paintings can seem sketchy and unfocused compared to Manet’s bolder forms and colours. Her city view in this exhibition seems downright depressed, perhaps reflecting her trauma over the Franco-

Prussian War. Or take their beach paintings on loan from the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (weirdly hung here top-to-bottom instead of side-to-side), each featuring sailboats in the distance. With minimal brushwork, Manet captures the taut curve of a mainsail shaped by the kinetic energy of the wind. Morisot’s sailboats are daubs of paint bobbing about, no sense of motion or direction. As a feminist who wanted to fall in love with her work, I am sad to say the direct comparisons did not help her cause or mine. Maybe I am too conditioned by the Modernist (read: male) project of Cézanne and other Post-Impressionists, but Manet’s economy of form and gesture proved startling, moving, in picture after picture, eclipsing Morisot’s more diffused approach.

Just one year ago the Legion of Honor hosted a larger Impressionist survey, Mary Cassatt at Work. Bringing nearly 100Cassatt works to San Francisco, it gave visitors a chance to fully inhabit and appreciate her pastel-hued and blue-tinted world of nannies nursing babies and women busy knitting. With Manet & Morisot the double focus prevents us from real immersion, until the very end. Devoted to Morisot’s work after Manet’s death, the final gallery is filled with paintings of her daughter Julie at different stages, from the toddler playing in the sand to the teenager playing the violin. At last, this gallery gives us the time and space to sink into the shimmery, but never fake-cheery, world that Morisot created: one where she used quick flicks of the brush to grasp at the feelings that make everyday, fleeting moments worth remembering.

- Manet & Morisot, Legion of Honor, San Francisco, until 1 March

- The show will travel to Cleveland Museum of Art, 29 March-5 July 2026

- Curator: Emily A. Beeny

- Tickets: $35 (concessions available)